When I first planned this series, I expected to write four posts, including the introduction. But since then I thought of one more topic that I should address.

Up till now, I have addressed all these topics from the outside, as a philosophical observer from Elysium or the Moon, without any indication that I know what it feels like to be on the inside of this question, to have it be about you. And so it is fair to ask, What about the very real suffering of people with gender dysphoria? When I sit here on the outside, placidly saying that surgery is dangerous and you can't force anyone to trust you, what do I have to say to the people who find that their fundamental identity is at odds with the physical body they find themselves in? Am I just totally insensitive to such a crisis of identity?

It's a fair question, and my answer may not be satisfying. In fact I have two answers. The first answer tries to speak to our ordinary, lived experience; the second is more abstract and metaphysical. In any event, I will give them both.

That's my first answer.

The second answer backs away from the personal point of view, and tries to look at the whole question from the perspective of classical Buddhist teaching.

You see, in Buddhism, your identity doesn't exist at all. Or rather, more exactly, when you dive deep down inside yourself to find the core of what is really You, you come up empty-handed. This is the doctrine of anatta, or "no-self." And all it means is that when you try to strip away the habits you've acquired from your friends, and the prejudices you acquired from your family, and all the other superficial affectations you got from wherever-you-got-them, ... that's all she wrote. There's nothing left that is truly You. To those of us who grew up in the West, in the shadow of René Descartes's ringing proclamation, "I think therefore I am," this sounds crazy. If I don't exist, then who is doing all the thinking that I hear inside my head? But Buddhism teaches that the thoughts can exist without a thinker, as just one more part of the whirl of existence that blows through like a raging tornado and then dissipates.

All this sounds pretty abstract. But look at it in concrete terms. Think about when you were six years old. Who was that person? What were your big concerns back then? Now how about when you were sixteen? Probably your photos show enough resemblance to when you were six that you can say they are pictures of the "same person" with a fair degree of reliability, but what was important to you when you were sixteen? What were you proud of? What were you afraid of? Is there any meaningful sense in which you can say that those two people were "the same" except that they shared a name and a history? Now how about when you were twenty-six? Or forty-six? Again, what's really the same? If you ask me these questions out of the blue, of course at first I'll say that all those are the same person. But when I think about it, ... well gosh, let's see:

- When I was six, my biggest enthusiasm was playing super-heroes.

- When I was sixteen, my biggest concern was to do well in high school.

- When I was twenty-six, I had just left graduate school and was trying to find my way in a new marriage.

- When I was forty-six, I was responsible for two children and my marriage was already unravelling.

Today it's this. Tomorrow it will be that. And the day after? Who can even see that far ahead?

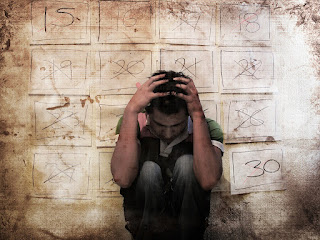

So yes, many people find themselves strongly committed to an identity that is not borne out in the visible and tangible world. It causes deep pain. It sucks. Really.

But also, it isn't solid. That might sound patronizing and I don't mean it that way. But over time, one identity shifts into another. It's a mystery to me how this happens, but it happens.

For all that anybody knows, it might happen to you too.

__________

* Once again, please remember what I said in a footnote to part 2 in this series, that when necessary "I still use he and his as the unmarked (generic) third-person singular personal pronouns.... [and that when I do] I am emphatically not trying to make a political point."